Booking.com is a best-in-class share that has been a prominent feature in our top 10 client holdings for the last few years. It has both taken market share and maintained some of the healthiest margins in the travel industry. Thalia Petousis takes us on a journey to unpack its success.

Prior to the internet revolution of the 1990s, travel planning was an arduous process. Aspiring tourists accumulated physical inventories of paper maps, guidebooks, traveller’s cheques and entertainment brochures. Notepads filled with local language phrases and word-of-mouth recommendations were crammed into overflowing backpacks. It was against this messy backdrop that Booking.com would come to join the league of some of the greatest companies in the world that cut their teeth by solving real-world problems and unmet customer needs.

Booking.com is the amalgamation of three internet start-ups that each began with barely more than a single employee and an idea. Geert-Jan Bruinsma, a computer science student in Amsterdam who had also done a brief stint as a hotel night porter, set up a booking website named Bookings.nl in 1996 using a single server under his desk. His goal was to make the difficult process of booking hotel rooms in foreign countries, which often involved translation issues and complex contact details, much simpler. In the US in 1997, Priceline.com was the brainchild of Jay Walker, who developed a “name your own price” travel system whereby a customer would bid what they were prepared to pay for a particular flight or hotel booking – the inverse of the traditional customer-retailer relationship. This business model might easily have become a casualty of the dotcom bubble were it not for a chance meeting at a travel trade show with Bruinsma’s Bookings and a third travel start-up – ActiveHotels.com. ActiveHotels.com was founded by two cousins in the UK who felt that they could build a better and more locally relevant business than Expedia, Hotels.com and Lastminute.com by focusing on niche independent hotels.

Booking.com’s best-in-class profit margins are not only thanks to its offering, but also the result of a culture of efficiency and cost control …

Fast-forward to today, and those three start-ups have become Booking.com, the world’s largest online travel agency, offering 31 million accommodation room listings and handling 1.1 billion room night bookings in 2024 alone.

An investor who bought the share 25 years ago would have earned a 16% annualised dollar return on average in every following year, or almost double the return of the US stock market. In 2024, Booking.com handled a gross bookings value of US$166bn – almost double that of its closest competitor. It charged an average revenue commission of 14%, on which it earned a net profit margin of 24%. This is almost three times wider than the net profit margin of the next largest travel player, Expedia. What has contributed to Booking.com’s success?

The key to Booking.com’s business-class competitive edge: Letting the customer choose

Echoing back to Bruinsma’s vision, Booking.com was founded on the key principle of always giving your customer flexibility – from transacting in their own language and currency to making payment via a local app, as well as “naming the price” by filtering on the accommodation’s cost. Perhaps most importantly, Booking.com saw the future in allowing each customer to carefully curate their own vacation by offering them the flexibility of any accommodation type they desire – from hotels to apartments and campsites, or even a glass-and-ice igloo from which to watch the Northern Lights in Finland. As the company watched the demise of package holiday giants, it hardened its resolve to always give the customer as much choice as possible, regardless of the unit economics of that particular accommodation. In fact, the average daily room rate across all accommodations booked on Booking.com was US$134 in 2024, which was virtually unchanged from 2007 – harking back to Priceline’s desire to let customers state their own budget.

As budget travel has gained popularity, customers have increasingly chosen aparthotels – which combine the features of a hotel with the convenience of a serviced apartment – and other alternative offerings. On this point of flexibility, Booking.com’s chief executive officer, Glenn Fogel, has often remarked that a customer will start out on their platform looking for a niche private apartment and end up booking at a chain hotel, or vice versa, as their itinerary fleshes out and they change their mind. Booking.com must therefore allow them that change and must never keyhole their offering into what makes the most sense from a corporate profitability standpoint.

The competitive moat inked over decades

Booking.com’s competitive moat also rests on its scale. Its app, via which it sells more than 50% of its room nights, has been downloaded more than 500 million times by customers. These network effects work in both directions: Hotels are attracted to the online travel agent with the most customers, who are, in turn, attracted to the online travel agent with the most hotels. The barrier to entry this creates is formidable. New entrants struggle to match both Booking.com’s supply and its technology, which has been built up via years of mergers, acquisitions and in-house development.

Booking.com also has refreshingly conservative accounting practices, a pristine balance sheet, and it runs a structural net cash position.

When Google launched its Book on Google product using a standardised application-processing interface to onboard hotels, there were market concerns about an existential threat to Booking.com’s business. These fears were eventually proven unfounded – the contracts that Booking.com had inked over decades by sending armies of people to roam the world’s travel destinations and sit down for coffee with independent hoteliers in the far-flung islands of Greece and remote areas of the Italian Dolomites, were too difficult to replicate. Added to this, Google did not want the burden of customer-servicing responsibilities that Booking.com had perfected over years of call centre upgrades and itinerary management trial and error. Another consideration was that Booking.com is Google’s largest travel customer – contributing almost US$6bn to advertising spend per year, or 14% of Google’s paid search revenue.

Carving out an “independent” niche

Booking.com’s edge has also been in cornering the independent and European travel market, where it has a 67% share of EU online travel bookings, or 46% of total EU travel bookings. While chain hotels dominate in the US, Europe’s travel market – as well as its food offering – is interlaced with bespoke and niche independent players who reflect the continent’s cultural diversity. Given that independents often lack the in-house tech and budget to advertise widely, invest in state-of-the-art booking and payment systems, or manage a customer’s itinerary and ongoing booking support, Booking.com can add value and also get hotels “on the map”. Independent hotels in Europe that sign up to Booking.com can see up to 60% of their bookings come from this channel.

Pristine balance sheet and high free cash flow returns to shareholders

Booking.com’s best-in-class profit margins are not only thanks to its offering, but also the result of a culture of efficiency and cost control, and structuring its business around a variable expenses model to create a safeguard during travel downturns. The company has also built brand loyalty over time by leveraging its app and the associated direct customer revenue outside of hits from Google’s paid search.

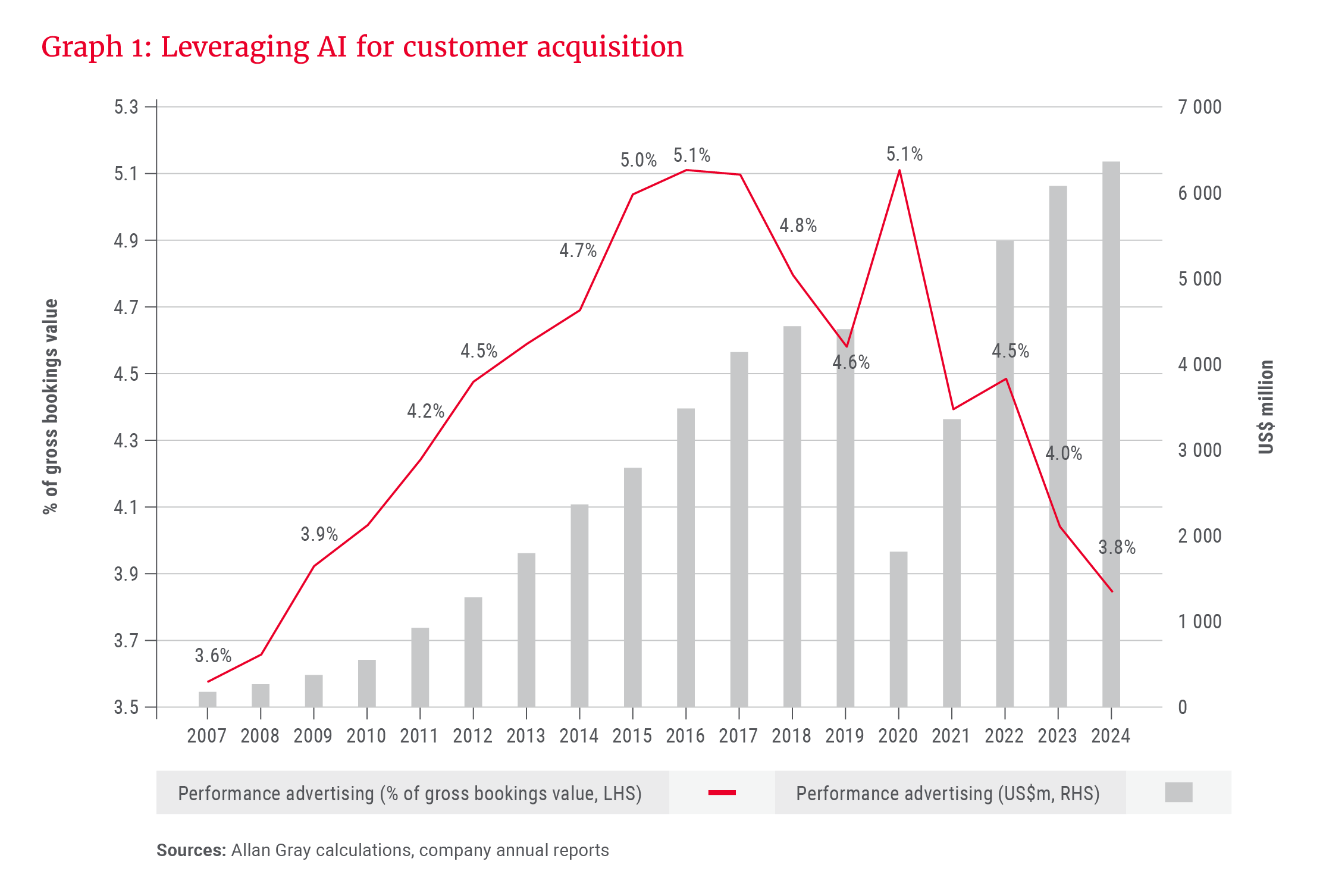

Although its performance advertising spend has risen from US$2.3bn in 2014 to US$6.5bn in 2024 – a 10% per annum capital growth rate – Booking.com has actually become more efficient at marketing spend over time, in part by leveraging AI algorithms to target customers better. As can be seen in Graph 1, Booking.com spent on average 3.8% per gross booking on customer acquisition in 2024 – lowering the figure from a peak of 5.1% in 2016 (ignoring the COVID-19 period), which translates into a 7% wider profit margin as a percentage of revenue.

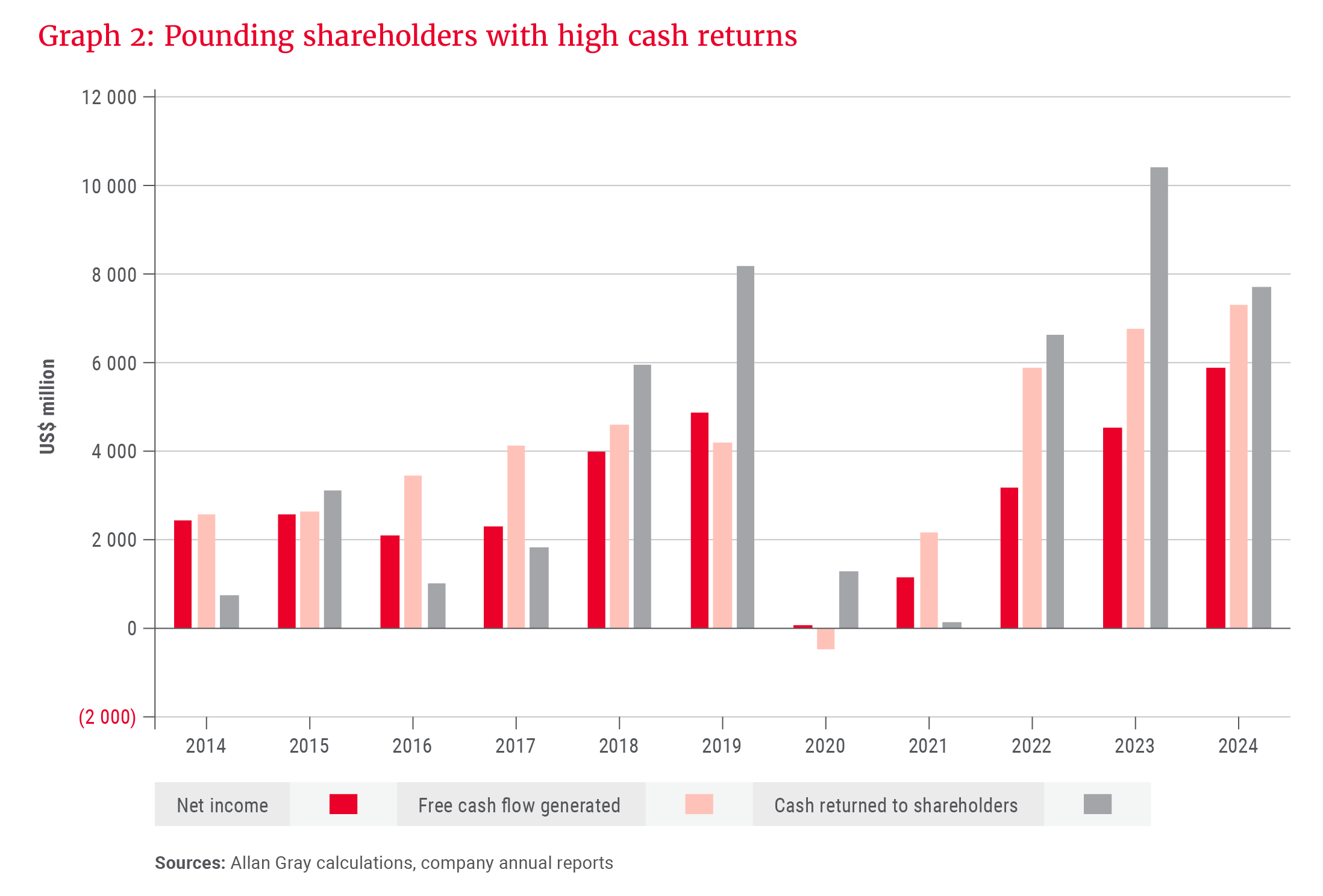

Booking.com also has refreshingly conservative accounting practices, a pristine balance sheet, and it runs a structural net cash position. Over 2014 to 2024, it made US$148bn of revenue and US$43bn of operating profit. This translated into 100% free cash flow conversion, and it returned this full US$43bn amount to shareholders via share buybacks and dividends – as shown in Graph 2.

Is Booking.com too big to grow further?

Given Booking.com’s dominant position and the threat of AI disruption, some argue that the share is now mature, with few remaining growth prospects. We think that misses the mark for a few reasons:

Travel market leverage: Accommodation revenue has continued to grow at “GDP plus-plus” for structural reasons: When people achieve larger incomes, they spend incrementally more of that additional income on travel.

Incremental revenue growth opportunities: Although Booking.com is the dominant online travel agent in Europe, future revenue growth should be underpinned by the ongoing incremental shift from offline to online travel as the younger population replaces older tourists who still use legacy methods of travelling, like physical travel agents. Booking.com has also been taking a larger share of the alternative accommodation, US and Asia-Pacific markets, where it is far from dominant.

Booking.com's battle cry is to make it easier for everyone to experience the world, converting lookers into bookers …

The Connected Trip vision: Booking.com has been talking about its holy grail Connected Trip for many years, and AI might just be the tool that allows this vision to be realised. The idea is for Booking.com to provide a seamless and personalised end-to-end experience – a one-stop shop for travellers. Booking.com hopes to reduce travel friction for users while creating new revenue streams by capturing a larger share of travel wallets through the cross-selling of flights, tours, dining and “experiences”. The latter is a highly fragmented travel vertical, whereby tourists book bolt-on tours via a litany of sometimes unreliable websites. This vertical is economically attractive because customer acquisition costs can be nil for incremental revenue: Booking.com already knows, based on bookings, when a customer will be in a specific location. From there, it can easily market a tour or activity that fits seamlessly into the customer’s itinerary. Although AI trip planners are still somewhat unreliable, once developers figure out how to clean and tokenise the input data to generate sensible and replicable itineraries, Booking.com can slot its offerings into ChatGPT’s itinerary output to create this seamless booking vision. To this end, Booking.com recently added supply to its sites of in-destination tours and activities in 1 700 cities.

Margin leverage opportunities: Booking.com can grow margins via continued advertising efficiency gains. By driving marketing leverage, it can also achieve general leverage as it does not need another office building or layer of management for its incremental traveller. Booking.com can also continue to lower fixed costs as it utilises AI call centre chatbots and reduces its physical footprint.

Converting lookers into bookers

Booking.com's battle cry is to make it easier for everyone to experience the world, converting lookers into bookers, and offering would-be travellers freedom of choice and the ability to travel within their stated budget. In addition to changing how we travel, during its rise, Booking.com also turned all the other online travel agencies into converts, reshaping how they thought about (narrower) commissions and forcing them to add an option in many listings to cancel the booking with a full refund.

Like most of the greatest acquisitions in internet history, Priceline's inspired purchase of Bookings.nl and ActiveHotels.com saved the company from falling into obscurity, cementing its spot as a market leader. With its Connected Trip vision, Booking.com is fighting off complacency by keeping its eye on a bigger prize.

Explore more insights from our Q3 2025 Quarterly Commentary:

- 2025 Q3 Comments from the Chief Operating Officer by Mahesh Cooper

- Peeling back the layers in Remgro and Reinet by Jonty Fish and Malwande Nkonyane

- Orbis Global Equity: Biotech breakthroughs in a crowded market by Graeme Forster and Mo Zhao

- How to unlock value through offshore investing by Horacia Naidoo-McCarthy and Radhesen Naidoo

- The ALSI's evolution in a changing economy by Matthew Patterson

- How to safeguard your investments by Twanji Kalula

To view our latest Quarterly Commentary or browse previous editions, click here.