At Allan Gray, we think carefully about the executive remuneration policies of companies in which we invest our clients’ capital. Why is this a worthwhile exercise? The answer lies in how companies are governed and the outsized impact that executives’ incentives often have on the total shareholder return of the companies they manage. Pieter Koornhof explains.

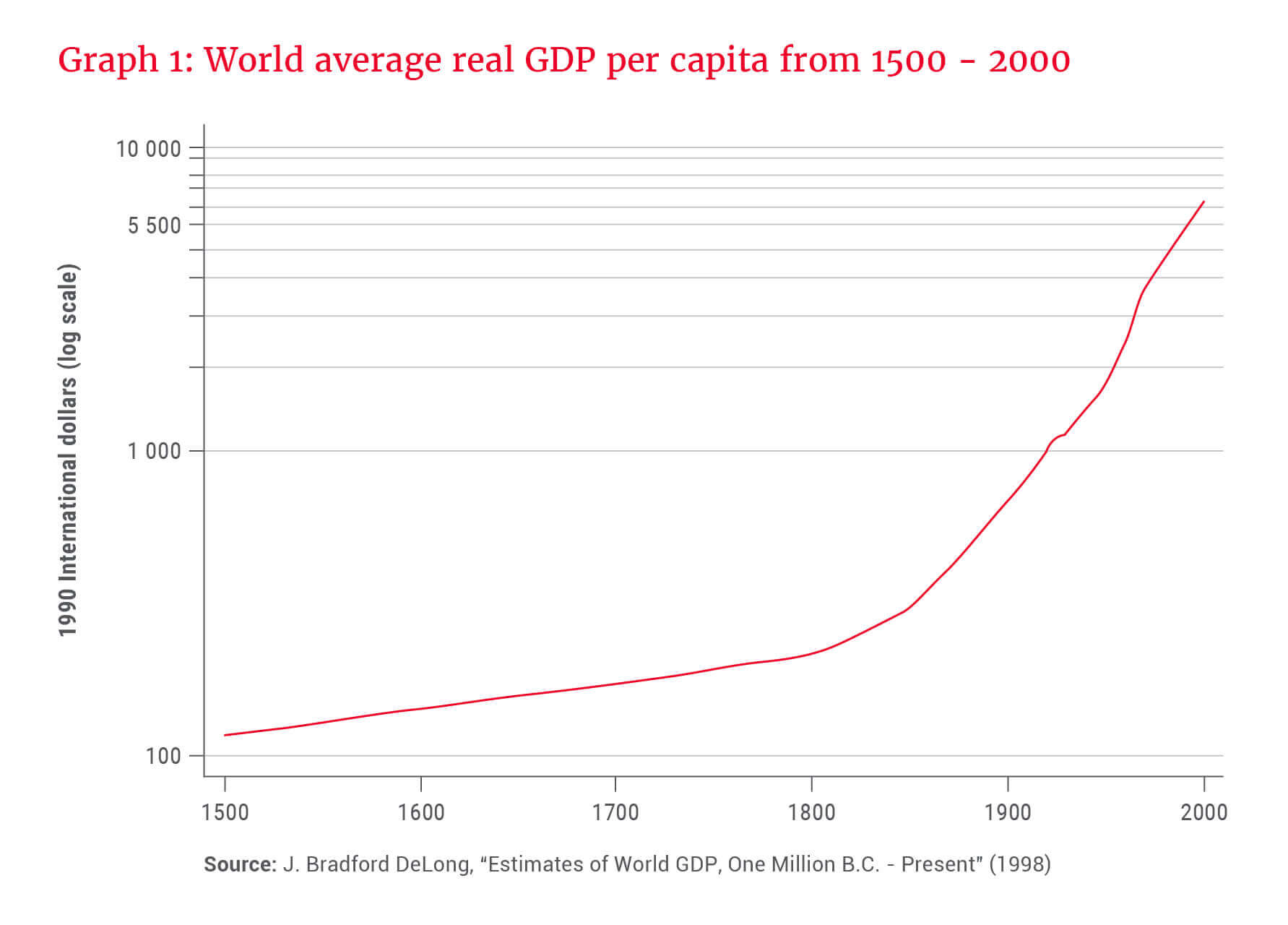

The world’s first publicly traded company, the Dutch East India Company (DEIC), was founded in the early 17th century. This marked the dawn of modern capitalism as it was the first time that the public (everyday people like you and me) could buy shares in a company that was managed by someone else. This separation of ownership from management was crucial as it enabled entrepreneurs to raise capital from the public to fund new business ventures and technological innovations. This, in turn, paved the way for the Industrial Revolution that heralded an era of unprecedented economic progress, as reflected in Graph 1.

Public companies have been an enormous benefit to mankind, but their structure presents inherent problems as soon became apparent at the DEIC. The DEIC was formed in 1602, and experienced its first governance crisis as early as 1609, when executives raided the company’s coffers to enrich themselves at the expense of shareholders. And not long after, in 1622, there was the first shareholder revolt when it emerged that executives had been cooking the books and shareholders demanded a proper financial audit of the company.

What went wrong at the DEIC? Economists call this type of problem a “principal-agent problem” or “moral hazard”. In the context of public companies, the root cause of the problem is that the incentives of executives who manage the company day-to-day are not always aligned with the long-term interests of shareholders, the owners of the company. The world has come a long way since 1622, yet today, despite centuries of advances in economics, contracting theory and corporate law, the principal-agent problem between shareholders and executives still frequently results in poor outcomes for stakeholders in public companies.

The solution and its shortcomings

Executive remuneration policies have arisen as the accepted solution to this problem. Many executives work hard because they enjoy their jobs, or because of some other intrinsic motivation, but some inevitably game the system for monetary gain.

The idea with executive remuneration policies is to structure the remuneration so that the executive gets a bigger payout if the company performs well (which also benefits shareholders and other stakeholders), but a smaller payout if the company performs poorly. In theory, executive remuneration policies should nudge executives to act in shareholders’ long-term best interests. However, for a number of reasons, it is rarely that simple in practice.

Remuneration committees are composed of non-executive directors, who are unlikely to know the company nearly as well as the executives who manage it day-to-day. This information asymmetry leaves executives well-positioned to convince the remuneration committee that good performance is due to their brilliance, while poor performance is due to external factors outside of their control.

Similarly, it is difficult to set performance targets that are sufficiently stretching, and remuneration committees often have to rely on executives for guidance on this. However, it is in executives’ self-interest to low-ball the targets to make them easier to achieve, and in doing so ensure big bonus payments.

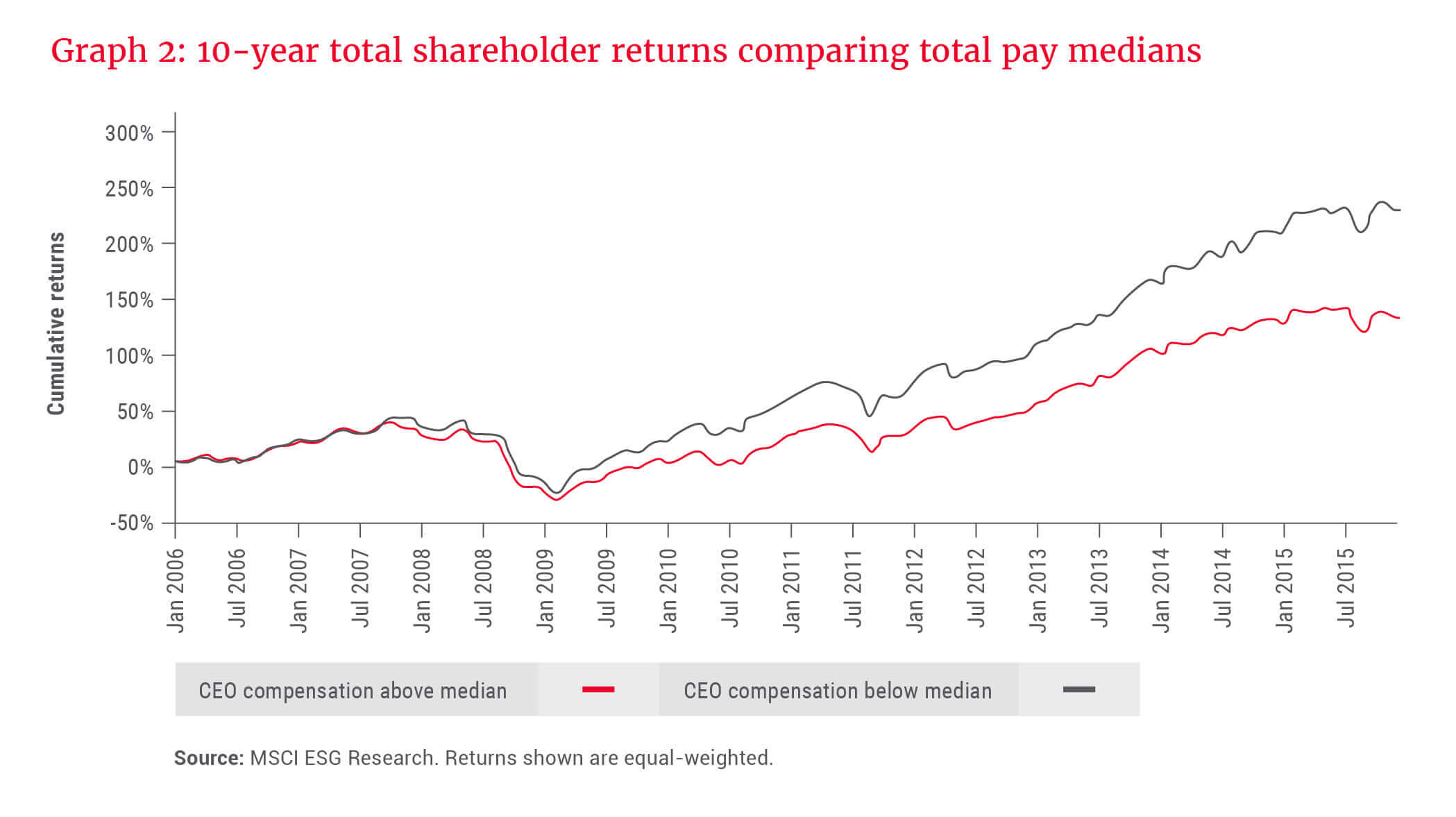

It is also tempting to think that to get the best executives, companies must pay them the most. Research by MSCI has shown that this is not the case: Graph 2 illustrates that companies whose chief executive officers’ remuneration is less than the average of peers actually outperform over long periods of time.

It is difficult to determine the optimal performance factors, i.e. the metrics on which an executive’s performance should be measured when determining their remuneration. Many performance factors can be gamed or, alternatively, may incentivise the wrong behaviour, often resulting in value destruction.

At Sun International and Famous Brands, for example, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) was the primary performance factor for executives’ remuneration, which possibly contributed to executives pursuing expensive offshore acquisitions. Unfortunately, EBITDA is often a flawed performance factor, as it does not factor in the cost of capital and the capital expenditure necessary to maintain the EBITDA.

The outcome was that, while executives at these companies received big bonuses for achieving their targets, shareholders suffered as the acquisitions were value-destructive. In addition, despite a remuneration committee’s best intentions, even sensible performance factors sometimes have unintended consequences.

Another common pitfall is that executive remuneration policies are often quite short term, with very little remuneration tied to how the company performs over the long term. Short-term results often have a lot of noise in them and it takes time before it can be determined whether capital allocation has been prudent. As such, if a company is undertaking a capital project or acquisition and it is expected to take five years before it becomes clear whether or not it has been value-accretive, there is a fundamental misalignment if executives receive most of their remuneration after one or two years.

So how can these shortcomings of executive remuneration policies be overcome?

Allan Gray's Approach

When looking at the remuneration policies of companies we invest in, our guiding principle is that executives should have “skin in the game”. This is the best way to ensure that they act in the long-term best interests of shareholders. To achieve this, the following is necessary:

- Executives should build up a material long-term shareholding in the companies they manage.

- Most of executives’ remuneration should be tied to the long-term performance of the company, with “long term” meaning at least five years.

- The performance factors used must be difficult to game and must incentivise prudent capital allocation, not value-destructive behaviour.

- The quantum of executives’ total remuneration should not be excessive compared to that of executives in other companies in the same industry and/or of a similar size.

We think a good outcome is when a company performs well over the long term and its executives are rewarded handsomely (but not excessively) for performance within their control. This is also beneficial to other stakeholders as a company is unlikely to create value for shareholders over the long term unless it also takes care of its staff, environmental resources, regulatory obligations and other stakeholders. We also actively try to guard against bad outcomes, such as executives getting big payouts when shareholders and other stakeholders suffer.

We carefully analyse the executive remuneration policies of companies we invest in. This research is done within the investment team as it is often an important component of the investment case for a company. Each company is different, so performance factors that work for one company may be inappropriate for another, and it helps if you have investment analysts who know the company well enough to tell the difference. We avoid box-ticking and try to approach each company with an open mind, while trying to be reasonably consistent across companies.

We also use various tools to help with this analysis, including a big data set we have built on the remuneration of most executives active at Top 40 and mid-cap companies. This includes details of various aspects of executive remuneration, including the quantum, structure, performance period and other relevant metrics.

We use engagements and proxy voting to influence remuneration committees to improve executive remuneration policies as we believe this can make a material difference to capital allocation and companies’ subsequent shareholder returns. Please see our annual Stewardship Report and Policy on Ownership Responsibilities for more details, both of which are available on our website.

While a good remuneration policy is no panacea, it is an important tool to ensure that executives have skin in the game and act in shareholders’ long-term interests.

We consider BHP Billiton’s executive remuneration policy to be well-aligned with shareholders’ interests for the following reasons:

- Most of the remuneration vests over five years. This is a long vesting period compared to that of most companies.

- The payouts are based on how the company performed compared to peers over the five-year period, with no payout if BHP underperforms its peers.

- The incentives are also share-based awards, meaning that over time, executives build a shareholding in the company.

Together, these factors ensure that executives have skin in the game. While this is no guarantee that BHP will perform well in the future, it is a good start.