As governments shift their national priorities in response to escalating geopolitical tension, global investors have to consider additional variables as they construct balanced portfolios. Alec Cutler, portfolio manager at our offshore partner, Orbis, explains how recent developments are shaping the Orbis SICAV Global Balanced Fund’s opportunity set.

The Orbis SICAV Global Balanced Fund’s 2025 performance has been encouraging, having comfortably outpaced its benchmark and peer group over the period. It’s helpful to recognise that the current strength was born of a period of relative performance pain. Many of the positions that contributed to recent performance were established during 2019 to 2021, when we were building exposure to stocks, currencies and commodities that were deeply out of favour at the time. Performance suffered during that period, not only because we were buying these so-called “losers”, but also because we were funding those purchases by trimming or exiting “winners”. Those winning positions had performed well but, in our view, had become less attractive relative to emerging opportunities, where the discount to our estimate of intrinsic value was much wider, even as investor enthusiasm for the winners continued to grow.

So where do we stand today? Have the areas of opportunity, and the investment themes they coalesced around, run their course? Performance from here will ultimately be determined by the markets, and we have exactly zero control over that. What we can control is maintaining a portfolio that remains attractively valued and well aligned with what we see as the biggest opportunities, and equally, the biggest risks. Many of these continue to relate to long-standing themes. In particular, our early concerns around critical energy infrastructure and defence have since evolved into a broader observation – one that reflects a world increasingly focused on resilience, security and strategic self-sufficiency.

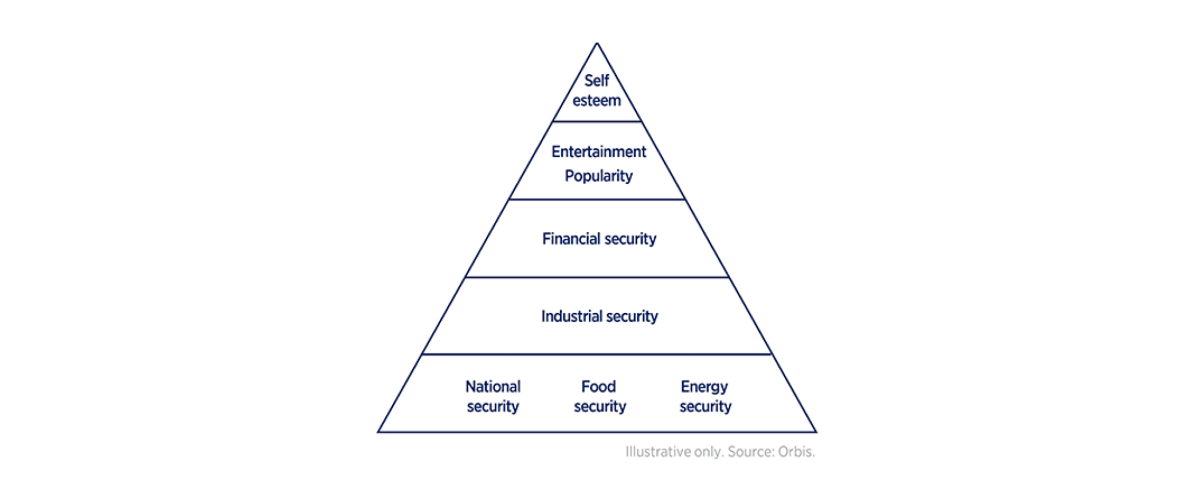

The hierarchy of needs of a nation

Many will be familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – the idea that humans are motivated by five categories of needs, with higher-order ones (such as self-esteem and entertainment) only emerging once more basic needs (like water, food, shelter, security and employment) are met. We believe this framework is also applicable to nations and offers a useful lens through which to understand the current global landscape – as illustrated by the diagram.

Furthermore, we believe that many developed nations – who have for some time been luxuriating in higher-order needs – have increasingly done so at the expense of the foundational ones, to the point where the base can no longer support the top of the pyramid. Governments are now being forced to reallocate resources from the top back to the bottom. A notable example is UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s February announcement to increase defence spending, funded by cuts to the overseas aid budget, followed in March by reductions to the welfare budget.

We believe this is happening now for a couple of reasons: a prolonged emphasis on higher-order goals at the expense of foundational ones and a broader geopolitical shift toward national self-interest. For decades following the fall of the Berlin Wall, developed nations benefited from what became known as the “Peace Dividend” – a period marked by relative geopolitical stability, expanding global trade and a belief that essentials like energy, security and food would remain abundant and affordable. Defence budgets were cut, and attention turned to social progress, environmental agendas and speculative growth. But in many cases, this came at the cost of resilience. Allied militaries weakened, and conventional energy sources such as nuclear and natural gas were sidelined in favour of renewables – contributing to energy crises, including the tripling of electricity prices in the UK and blackouts in Spain. The cracks in that once-stable foundation are now impossible to ignore.

This reordering has been accelerated by a broader retreat from global cooperation toward national self-reliance – a trend made more visible after President Donald Trump’s return to office, but one that has been building over the past decade and was sharply exposed by the supply chain failures of the pandemic era. Institutions that once defined global collaboration – such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization, the World Trade Organization and even the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – have become less effective or increasingly questioned. Recent actions by countries such as the United States and Israel further underscore this shift. Both have acted decisively in pursuit of their national interests.

Countries have a renewed appreciation that ultimately they are on their own. No one else is responsible for their security, energy or food supply, and certainly not their industrial success. As countries rebuild the base of their pyramid of needs, the implications for economies, industries and investments are only beginning to unfold. Our focus is twofold: to navigate the risks this transformation introduces and to capitalise on the underappreciated opportunities it creates.

This framework not only helps contextualise the macro environment – it maps closely to where we’re finding the most compelling investment opportunities through our bottom-up research.

While we’re not averse to investing further up the pyramid, it’s a part of the market where the balance of risk and reward has become less favourable – still crowded with capital and offering fewer mispriced opportunities. Years of social, political and market enthusiasm funnelled capital toward aspirational causes and consumer luxuries. This created fertile ground for strong performance, but also inflated expectations. As budgets tighten and priorities shift toward strategic essentials, those tailwinds may fade, and valuations leave little room for missteps. This means that the opportunities up top are few and far between.

That said, we’re not entirely absent from the upper tiers of the pyramid – just selective. Nintendo, for example, has seen strong early demand for the new Switch 2, a next-generation gaming console that builds on the success of its predecessor with improved performance and backward compatibility. While near-term earnings remain muted, Nintendo’s continued expansion into films, digital content and theme parks is helping unlock the full value of its beloved intellectual property. Meanwhile, theatre operators Cinemark and IMAX are positioned to benefit as audiences return to cinemas and the appeal of premium theatrical content endures.

When it comes to financial security, we’ve found more compelling value outside the perceived safe havens. With the US fiscal position deteriorating, sovereign debt in countries like Norway, Iceland and Brazil offers better risk-adjusted return potential in our view. Norway has no net debt, runs persistent surpluses, and is backed by a US$1.9tn sovereign wealth fund. Iceland, despite its frontier market label, offers high-yielding A-rated bonds supported by strong governance, a disciplined central bank and a straightforward economy anchored by abundant geothermal energy, tourism and fishing. Brazil, while more volatile, compensates investors with double-digit yields and a very undervalued currency –underpinned by a credible monetary authority and export revenues less tied to global trade cycles. This reflects Brazil’s commodity-heavy export base, particularly in iron ore and agriculture, where demand is driven more by China’s domestic consumption than its export sector, making Brazil’s revenues less sensitive to swings in global manufacturing and trade. Across all three, we see attractive yields in underappreciated currencies, offering diversification and a meaningful margin of safety.

Further down the pyramid, in industrial security, we’re focused on companies enabling the physical and digital backbone of successful modern economies. This includes both the semiconductors powering AI and connectivity, and the infrastructure firms rebuilding the systems that support them. On the semiconductor front, we own businesses such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Samsung and Micron – all benefiting from secular demand for AI, computing and connectivity, yet still trading at reasonable valuations compared to many of the AI-infatuated names capturing investor attention today. At the same time, the urgent need to reindustrialise and modernise critical infrastructure in the West is creating powerful tailwinds for a range of companies in our portfolio. Balfour Beatty is a global engineering and construction firm building everything from power lines to defence facilities. It also owns a portfolio of low-risk infrastructure, like toll roads, student housing and military accommodations, which it built but now collects rent from, providing a steady stream of recurring income. Keller, the global leader in geotechnical engineering, plays a foundational role early in the construction process – typically getting paid first while avoiding much of the project risk. MasTec, a specialist in infrastructure installation, is helping to modernise the grid as ageing energy systems face rising demand. And Generac, best known for residential generators, is becoming increasingly important in providing backup power for data centres and industrial users as electrification accelerates and grid reliability deteriorates.

National security, long overlooked by markets, has re-emerged as a strategic priority. Europe has been galvanised to boost defence spending and infrastructure investment in response to growing geopolitical risks and a requirement to reduce reliance on the US. We began building exposure to defence stocks five to six years ago, when they were deeply out of favour. That contrarian positioning, rooted in valuation discipline and a clear-eyed view of geopolitical realities, has since paid off. While we’ve trimmed most of our holdings after strong gains, we continue to own a number of high-quality aerospace and defence contractors – among them Leonardo, Rolls-Royce Holdings and BAE Systems in Europe, and Hanwha Aerospace and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Asia. As mandated defence budgets claim a growing share of GDP, we believe these businesses are well placed to benefit from a prolonged period of increased investment in security and strategic capabilities.

As governments confront the hard realities of national resilience, defence may have led the way, but energy is proving just as urgent and arguably even more fundamental. As we’ve written previously, investor sentiment has shifted from a strong focus on renewables toward a broader appreciation for what’s practical and scalable. That shift is still underway, presenting underappreciated and mispriced opportunities with plenty of runway. Kinder Morgan, with its vast natural gas pipeline network, plays a critical role in delivering the reliable electricity the world increasingly needs. Siemens Energy, once cast aside, is now benefiting from growing recognition of the value of its gas turbine and grid equipment businesses, especially as AI data centres demand not just more gas but the switchgear, transformers and infrastructure Siemens makes. Prysmian, a leading manufacturer of power cables, plays a vital role in updating and expanding the grid – from onshore transmission to offshore wind connections. Doosan Enerbility, a Korean engineering firm, brings rare and trusted nuclear power plant delivery capabilities. And Shell remains compelling for its strategically important gas business, which is being gradually rerated as energy pragmatism returns.

In our view, this reordering of national priorities marks a structural reset, not a passing phase. As capital flows back to the foundations of each nation’s needs, we endeavour to skate to where the puck is going, not where it is now – seeking opportunities where solid fundamentals and resilient demand drivers are paired with compelling valuations.