Mega-cap technology companies have come to embody America’s market might – innovative, dominant, and seemingly unstoppable. Yet history suggests that when leadership becomes this narrow, the opportunity for investors often shifts elsewhere. Could the next chapter of American exceptionalism be written not by its biggest companies, but by the rest of the market they’ve overshadowed? Simon Skinner, from our offshore partner, Orbis, discusses.

Key takeaways

- Concentration risks: US exceptionalism of the last decade has become dependent on a handful of mega-cap stocks. Just seven companies currently account for more than a quarter of the US S&P 500 Index.

- Valuation gap: Investors are also paying the highest prices for the most crowded part of the market. That is a dangerous combination. The 10 largest companies in the S&P 500 Index trade at 34x earnings, compared with an average of 22x earnings for the remaining 490 companies.

- Looking beyond the obvious: We’re finding compelling opportunities within the healthcare sector and founder‑led companies that we believe combine durable economics with long-run AI tailwinds, without paying “headline” AI valuations.

When one area of the market delivers so consistently for so long, it’s easy to forget an uncomfortable truth: even the best investments become vulnerable when they get too crowded. Today, the “American Exceptionalism” story of the last decade has become a concentrated dependence on a handful of mega-caps. Just seven US stocks – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla (the so-called Magnificent Seven) – have powered nearly all of the S&P 500’s gains in 2025 and now account for more than a quarter of the US index.

The result has been a challenging environment for active managers. Those who have tried to look for bargains among the laggards have been punished severely – if not already fired by their clients! Meanwhile, those who blindly followed the herd have been handsomely rewarded. With so few active investors willing or able to do anything but follow the crowd, we are reminded that, historically, it has been exactly such dynamics that have created the conditions for sharp and extended reversals.

At a time when macroeconomic and geopolitical risks feel as unpredictable as ever, diversification matters.

Crowded, fragile and expensive

On top of extreme concentration risk comes valuation risk. The 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 now trade at a lofty 34x earnings, as shown in Graph 1. While they may be fantastic businesses, investors are paying the highest prices for the most crowded part of the market. That is a dangerous combination – and leaves little room for error if the fundamentals fail to keep pace with expectations.

Outside the 10 largest names, the remaining 490 trade at a more reasonable 22x earnings on average. But a simple price-to-earnings valuation masks the true extent of the euphoria in the largest US stocks. US profit margins are also near cyclical highs – the stellar returns of the Magnificent Seven have been driven not just by rising valuations, but also by huge levels of earnings growth.

The 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 now trade at a lofty 34x earnings...

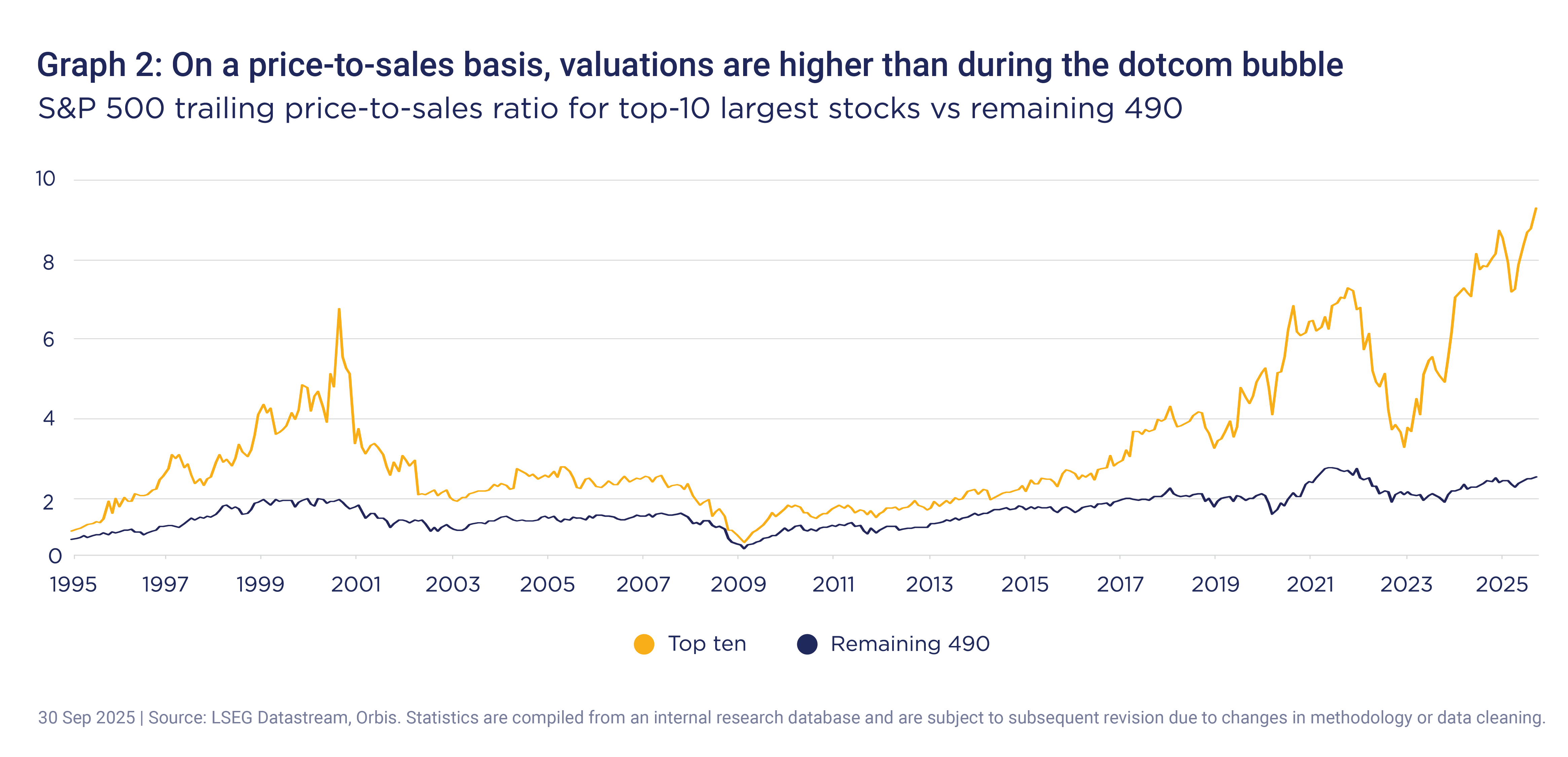

Stripping out the effect of increased profit margins by looking at valuations on a price-to-revenue basis, we can see the enormity of the valuation gap between the top 10 US stocks and the rest. Currently, the 10 largest US companies trade at valuations that are three times higher than the remaining 490 names, at levels that surpass even the height of the 2000s dot-com mania, as shown in Graph 2.

Not only is this valuation gap wide, it is also a striking reversal from much of the past 20 years, when the rest of the market regularly traded at a premium to their mega-cap peers.

Overlooked opportunities in the US

Happily, the US is a large place, and when the spotlight shines brightly on the largest names in the index, there is often plenty of value to be found elsewhere. Two areas of neglected opportunity stand out to us – healthcare and entrepreneur-led companies.

Healthcare combines resilience with powerful long-term growth drivers. Ageing populations, breakthrough biotech innovations, and the growing need for specialised services are reshaping the sector. Yet despite these structural tailwinds, healthcare stocks – including the very largest names – have lagged the market’s recent rally, leaving select opportunities attractively priced.

Our investments span a wide spectrum. Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Insmed are advancing cutting-edge therapies. UnitedHealth Group and Elevance dominate US managed care, with scale and data advantages that are hard to replicate. Steris leads in sterilisation and infection prevention—an essential, recurring service. Bruker provides precision instruments that underpin both academic and industrial research. We believe these are businesses with defensible niches and steady demand, largely insulated from the market’s obsession with a handful of mega-cap tech stocks.

We also find compelling opportunities in companies where the founder remains deeply involved and heavily invested alongside shareholders. Such leaders tend to think long-term, take calculated risks, and build with resilience in mind. Our experience suggests that founder-run companies are more agile, more decisive and more willing to take appropriate innovation risks – all of which position them ahead of peers as the available technology landscape shifts.

Interactive Brokers exemplifies this alignment—founder Thomas Peterffy still owns the majority of the company. Others, such as QXO and Corpay, are backed by proven entrepreneurs with a track record of building durable businesses across multiple cycles. While these companies are not immune to volatility, their governance and ownership structures create strong incentives to focus on value creation over the long haul.

Real diversification comes from businesses with durable economics, defensible positions, and leaders who can navigate uncertainty with conviction.

In many of these cases, we can see long-term opportunities for AI applications to materially improve these businesses – for the time being, these are not contemplated by other investors who are seeking obvious “AI plays”. As patient, long-term investors, we are happy to wait for these impacts to be evidenced in the fundamentals of these businesses. Over decades of implementing the same approach, we know that sooner or later, fundamental value is reflected in equity prices.

At a time when macroeconomic and geopolitical risks feel as unpredictable as ever, diversification matters – but not the cosmetic kind offered by a benchmark dominated by stocks which are all largely reliant on a single technology bet. Real diversification comes from businesses with durable economics, defensible positions, and leaders who can navigate uncertainty with conviction. In this environment, the edge doesn’t come from owning everything – it comes from having the courage to be selective, and the discipline to avoid the rest.

This article forms part of Orbis’ Six courageous questions for 2026. Explore more insights from the series:

- Is the world’s safest currency actually the riskiest? by Nick Purser

- Are you swimming in the right water? by Graeme Forster

- Which risk runs deeper: owning or avoiding emerging markets? by Stefan Magnusson

- Is AI a bubble, or is the best yet to come? by Ben Preston

- What if Trump is right? by Alec Cutler