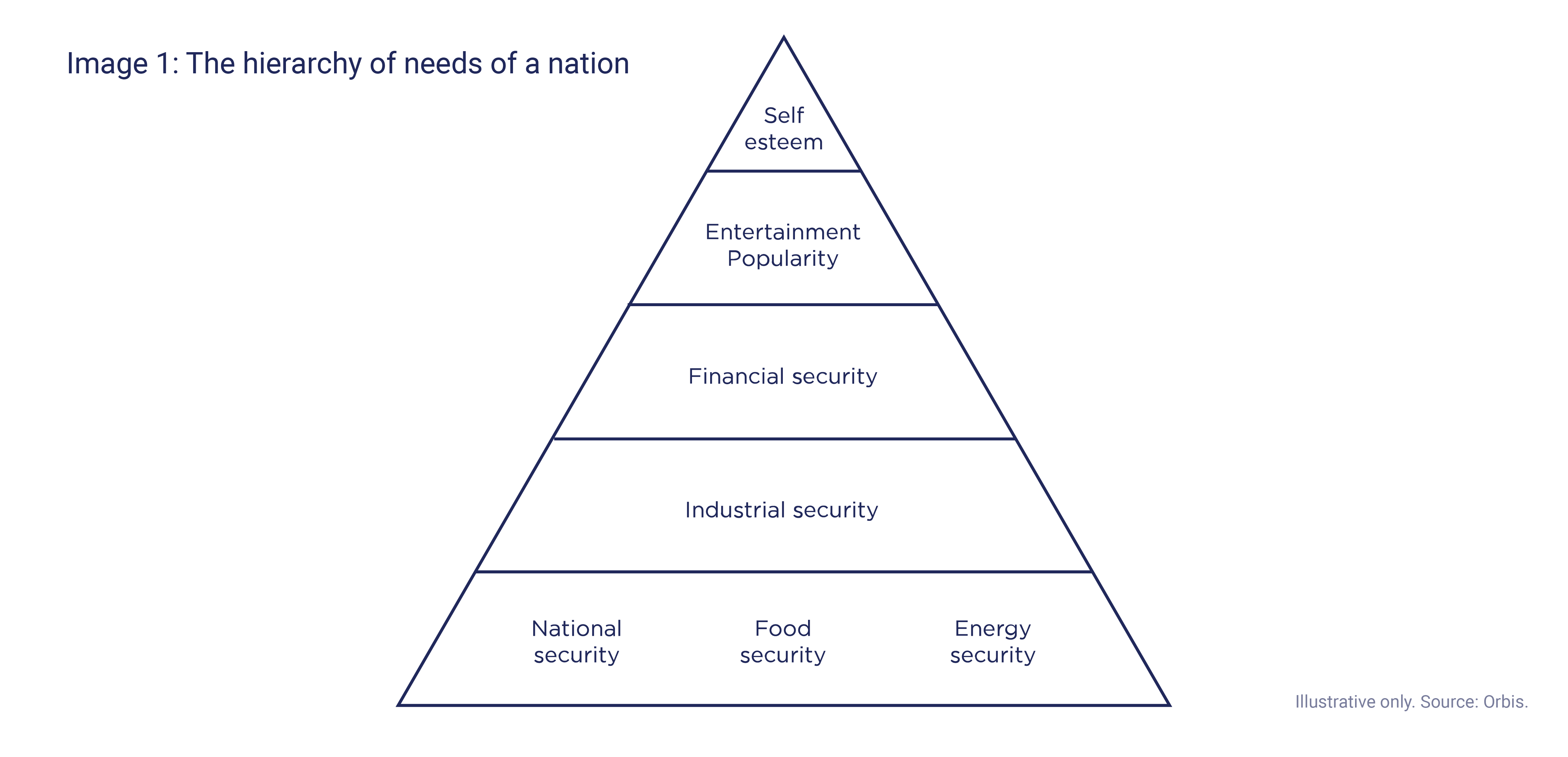

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs framework helps us understand both today’s shifts and the implications for markets. While capital was flowing towards the top of the pyramid – now crowded and expensive – sectors at the base were left underfunded. As nations refocus on energy, security, and industrial strength, the companies serving these essential needs are emerging as some of the most undervalued and enduring opportunities in global markets. Alec Cutler, from our offshore partner, Orbis, discusses.

On two big trends, President Donald Trump may well be right:

- Nations must rebalance from aspirational wants towards foundational needs.

- Nations can no longer depend on global support, so they must rebuild self-reliance.

Trump’s own policies have accelerated these trends and made them more visible, but the seeds of both shifts predate his presidency by years.

The pyramid of needs

To understand these changes, we borrow a concept from psychology. Many will be familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as shown in Image 1: the idea that humans must secure basic needs like food and shelter before pursuing aspirational wants such as entertainment and self-esteem. We believe the same framework applies to nations. Without military, energy, and industrial security, societies have little hope of pursuing a happier future.

How we got here

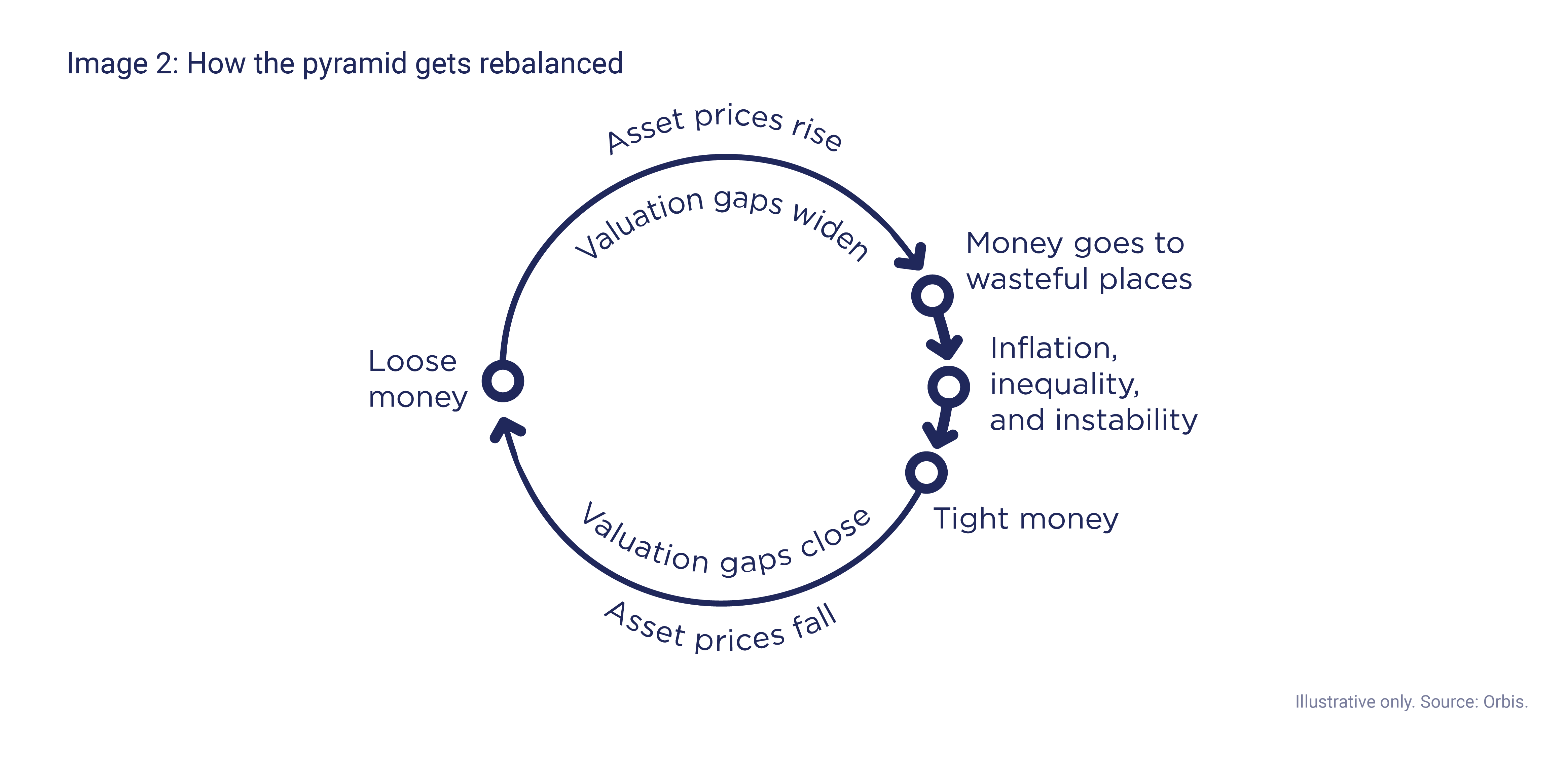

In recent decades, this pyramid has been upended, as shown in Image 2, initially by a very benign force: abundance.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the West reaped the “Peace Dividend” on defense spending. A decade later, China joined the World Trade Organisation, accelerating globalisation and letting consumers get goods cheaply from anywhere in the world. A decade after that, the shale revolution in the U.S. brought down energy prices globally. Throughout this period, rich nations welcomed millions of economic migrants. With an abundant supply of goods, energy, and workers – and less fretting about defense – society felt its basic needs were met. Inflation was low, allowing interest rates to decline. Money became abundant.

This sets off a cycle. When money is loose and society feels its basic needs are met, people start spending on luxuries and fun. Investors notice that and start throwing money at whoever has the grandest dreams for the future. Rising valuations signal to companies at the top of the pyramid to invest more, drawing in yet more resources.

This cycle plays out at the broad level of markets and the narrow level of companies. Mark Zuckerberg burns US$46 billion building the metaverse – a digital playground that no one else wanted to play in. Bernard Looney announces that BP, an oil and gas company, will cut production of its key products by 40%. Office sub-lessor Adam Neumann gets rich promising to elevate the world’s consciousness (and crashing WeWork). In times of abundance, money goes to wasteful places.

The dangers of imbalance: inflation, inequality, and instability

With resources rushing to the top of the pyramid, the base gets starved of capital. The result is shortages of things society actually needs. Those shortages cause inflation for normal people. Meanwhile, the Neumanns, Zuckerbergs, and Musks of the world are getting rich, increasing inequality. Put inflation and inequality together, and you get instability – society’s alarm bell that something needs to change. Conditions were ripe for Trump’s wrecking ball before he ever descended that escalator.

Rebalancing the pyramid: AI case study

Each step in the cycle sows the seeds of the next. Higher inflation attracts higher interest rates, and with money tighter, people think more carefully about where to invest it. But the cycle does not depend on central banks or governments. If the pyramid can get unbalanced organically, it can get rebalanced the same way. Here, AI is a great example.

“Put inflation and inequality together, and you get instability – society’s alarm bell that something needs to change.”

OpenAI chief Sam Altman has described AI as a bigger deal than the industrial revolution. It may be, and some of its applications are in crucial areas seen by companies or governments as existential needs. But his latest idea, Sora 2, is essentially a TikTok clone where all the videos are AI slop – prime top-of-pyramid stuff.

If you want AI, you need a whole bunch of things from the base of the pyramid. For a start, you need chips. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company makes all of the world’s leading-edge AI chips, whether they are designed by Nvidia, Broadcom, or AMD, yet it trades at a discount to those companies. AI is more memory hungry than conventional computing, yet the memory makers Samsung Electronics, SK Square, and Micron Technology also trade at discounts.

Chips are of little use without related infrastructure, much of which might be built by Balfour Beatty, a construction firm with a roster of anonymous data centre clients on its website. Those buildings sit on top of foundations laid by Keller, the world’s leader in geoengineering.

Data centres can’t connect to electricity grids without transformers from Siemens Energy and its competitors, who are less able to increase capacity because Silicon Valley has hoovered up the most talented engineers. Grid power has to come from somewhere, and has to be reliable. That bodes well for gas producer Shell and gas transporters Kinder Morgan and Enbridge. And amid all this, nuclear power is having a renaissance. As nuclear reactor providers to navies, BWXT and Rolls Royce are highly competitive for small reactor projects.

The rebalancing is happening already. Corporate customers are sending money towards the base of the pyramid, but in many cases, capital is still too scarce. For us, that’s appealing, as it suggests a higher return on that capital. For the businesses, it leads them to respond not by increasing supply, but by increasing prices. That inflation, in turn, promises to keep the cycle moving.

It took decades for the pyramid of needs to get this unbalanced. Trump may have accelerated the reckoning, but the great rebalancing is just getting started.

This article forms part of Orbis’ Six courageous questions for 2026. Explore more insights from the series:

- What if the real American exceptionalism now lies beyond America’s biggest stocks? by Simon Skinner

- Is the world’s safest currency actually the riskiest? by Nick Purser

- Are you swimming in the right water? by Graeme Forster

- Which risk runs deeper: owning or avoiding emerging markets? By Stefan Magnusson

- Is AI a bubble, or is the best yet to come? by Ben Preston